How to store, provide access to and make the most of your artistic, graphic and other visual collections.

What is a visual collection?

Collections can contain many and varied art forms using different mediums such as photographic prints, glass plate and film negatives, etchings and prints, paintings, cartoons and sketches, postcards, greetings cards, posters and more.

These materials may be housed together or separately as part of collections donated by individuals or organisations. Their size, medium and format mean that they may prove hard to store and maintain and will need special care and consideration if they form part of a local studies collection.

Storage

General advice:

All visual material is susceptible to damage. As with all single sheet materials, they can be placed in an appropriate sized inert polyester envelope which provides a certain amount of protection from handling. You can also use permanent markers to write catalogue numbers on the cover rather than the item itself.

Does the item need to be accessed easily? Perhaps not, if it has been digitised. In that case you can purchase inert polyester in ready-made envelopes, open either one or two sides, plus you can buy cheaper rolls which can be sealed using a specially designed machine, or just with the use of double-sided tape. These can then be stored in an appropriately sized box.

If you need public access, you can consider placing images in files, albums or hang covers from bars which can then be stored in filing cabinets.

Photographic material

Dating from the mid-19th century, photographs and negatives are an unstable medium and can degrade quickly if not stored in adequate conditions. Use acid-free envelopes to keep them as inert as possible; remove any card backings or mounts if you can. Keep them away from light, avoid damp conditions and store at as cool a temperature as possible. Keep an eye on the relative humidity too; a high RH level can be particularly damaging. The same will be true for film and glass plate negatives; the latter being very prone to damage (glass can crack easily). Do not fold or roll photographs and use acid free card and tissue for additional protection if necessary.

Photographic material is particularly susceptible to marking. Never use anything other than soft pencil (5B is best) to write on the back. Handle with gloves whenever possible and by the corners of the images when you cannot, as once a fingerprint is placed on the image, it cannot be removed from the original.

Printed material

Postcards can date from the late 19th century but prints can be a great deal older, although many prints date from the 18th century. Both mediums are more robust than photographic material, but the card and paper they are made of can still degrade over time. Store in acid-free boxes. Postcards can be stored in 4-pocket acid-free envelopes to save space. Prints can vary in size; always store flat wherever possible. It is advisable never to fold or roll prints. Modern items may include posters and greetings cards. Again, store in acid free conditions and, if possible, do not fold or roll posters as this will weaken them and make them more prone to damage.

Artworks

Watercolours require less specialist storage than oil works which may be better placed in your local museum or art gallery. Again, store in acid free boxes; use acid free tissue for additional protection if necessary. Flat storage works best. Do not fold or roll items; this will cause stress on the material and lead to further deterioration. Remove any backing which may react with the works or cause difficulty in storing the items correctly, including frames, mounts and metal clips etc.

Long-term preservation of materials

Consider the best place for visual items to be stored. The medium used to create many of them will be unstable in nature and they may be best placed in a specialist repository. If you have created a digital surrogate you can think about depositing the originals in your local archive or museum if they have dedicated storage facilities such as a climate controlled strong room, or in a regional repository, such as Hampshire Archives & Local Studies which is home to the Wessex Film and Sound Archive https://www.hants.gov.uk/librariesandarchives/archives/wessex-film-sound and contains the specialist storage facilities required for film.

Conservation suppliers:

- Conservation by Design (CXD): https://www.cxdinternational.com/

- Conservation Resources: https://conservation-resources.co.uk/

- PEL: https://www.preservationequipment.com/

Access (aka cataloguing and metadata)

Often such items provide rare and possibly unique images of local people, places and events. This means that they should be catalogued individually; these details are often lost when cataloguing at collection level. Specialist software such as MODES (the Museum Object Data Entry System) or CALM can be used to create individual templates for visual material types such as photographs, whilst Lancashire’s Red Rose Collections used an image management system to digitize and catalogue images whilst providing online access.

If you do not have access to specialist cataloguing software, you can use as little as an Excel Spreadsheet. Google Form or Microsoft Form allow you to set up a cataloguing form and then inputs the data into a linked spreadsheet which can be used as a finding aid. This can then be used to upload to an online platform at a later date.

It is essential to catalogue items in your collection to make them:

- Accessible for customers

- Locate the items easily

- Each piece of information should be in a separate field, so it can be easily manipulated at a later date.

- Follows the eighteen internationally respected Dublin Core principles so that information can be easily used in different projects and systems at a later date.

- An essential component of the cataloguing process is to be consistent with your data inputting to ensure that you create a robust, high quality finding aid. Certain data, such as place name, the way you enter a person’s name and locality type should be specified at the start of the process and strictly adhered to. After all, rubbish in, rubbish out – the quality of the finding aid will only be as good as the data that is put into it.

- Photographs may have also been catalogued in previous years. These can be harnessed, though you have to be aware that they may have been catalogued in different ways.

Sample set of fields:

Key information includes:

Type of object – for example postcard, photograph or print

Unique ID number – each item should have its own catalogue entry number. This is usually prefixed by the date it entered the collection (accession date) but not always; do whatever works best for you

Brief description – to include a description of the contents of the image and anything within it that is unusual or draws your attention. This can include costume, architecture, internal fittings or fixtures etc. Details of people in the image and the context surrounding it, for instance it may be a wedding or a stone laying ceremony.

Title (optional) – if you decide that your brief description should be longer than a line of text.

Long description (optional) – if the image is fascinating, you may wish to write a paragraph or two on the item. This can then be reused for marketing purposes.

Date – of the medium itself and of the contents of the image, for example this could be a modern copy of an old photograph; both dates will be needed to give an accurate record of the item. If an exact date cannot be determined even an approximate one is preferable to leaving this field blank

Keywords : Location – record the place the item relates to.

Keyword: Subject term – This can include a ‘locality type’ such as church or school. You can start with a basic list of terms which can then be built up as you go along if you do not currently hold any.

Keyword: Names – Individuals and companies.

Depositor – details of the person/organisation for provenance purposes, though avoid including personal details on public catalogues

Date of entry into the collection and the date of the catalogue entry

Creator/Production data – for instance, the name of the photographer or artist who created the item

Dimensions and condition of the item – useful when considering the fragility or difficulty of moving the item

Current storage location – this data is essential so that you can find the item quickly and easily

Rights data – has this image been checked for copyright? Are there any restrictions regarding its use? For more information about copyright, see the Copyright section of the toolkit.

Digitisation – has the item been digitised? If so, provide details of the whereabouts of the surrogate

Digitising collections

Visual materials are an amazing resource that can help to promote your local studies collection. A digitisation project can help you access the value of the collection. It can also help create surrogates that will extend the life of the original item, particularly if it is fragile as it will be handled less frequently and will allow it to be kept under stable conditions for extended periods. Scanners are useful for digitisation work, but a good quality SLR camera on a fixed stand is an alternative. Digitisation projects are a good candidate for Crowdsourcing to gain funds to buy digital equipment (see the Crowdsourcing section of the toolkit), HLF Funding and for bid funding.

During the digitisation process, try to alter the settings as little as possible. In this way you can attempt to keep the essence of the original image alive in the digital version, only manipulating any further copies you may produce (see ‘storage of digital items’ for further details). The only permitted changes are the “white and black” levels .

There are many scanners on the market, though the Epson Perfection V800 Film and Photo Scanner often comes out as a recommended choice. Though only an A4 scanner, it works well with slides and negatives and large images can be scanned in section and then “stitched” together with software.

Quality of digital images

To make the most of images for varied uses, it is best to digitise to as high a resolution as possible. If you can do this, it is also possible (where appropriate adhering to copyright law) to make income from your visual collections through the provision of high-resolution copies. Scanning at 1200dpi is a good choice as is maintaining the resolution of images captured by an SLR camera. Many projects suggest using 600dpi as a standard for prints, but higher specifications for negatives. However, you do need to ensure that your scanner can make images up to your selected quality as some scanners only “guess” for higher quality scans.

Storage of these images can be an issue long-term, so think carefully about which images you store and where. Save digital images in an industry standard format. TIFFs are ideal as they retain the pixels throughout the life of the image however many times it is viewed, unlike JPEGs. You can create additional low-resolution jpgs specifically for online use as and when you need them. For online use via social media, low resolution images are fine; even images around 520 pixels wide work well.

Think about the use of your images online. Be aware that they may get re-used and copied for free. You may want to watermark your images; if they are re-used and copied this gives you provenance and a way to promote your collection further. You can do this by adding text via Paint or free online tools such as watermark.ws. Do not use the copyright symbol unless you are explicitly the copyright holder. Instead, use the name of your organisation or ‘Courtesy of…’ to avoid confusion.

Storage of digital images

There are many ways to store digital images, but you will need to keep up with technological changes over time to ensure that your images will remain accessible in the long-term. You might be able to use your organisation’s current storage facility, although this may not be possible if you are creating many high-resolution images that will take up a lot of space. Instead, you could use external hard drives. Three copies should be made, with a working copy and two backups. At least one of the backups should be stored in a different building.

More recently, cloud storage is possible via external organisations. Think carefully about the long-term security of this and take advice if you need it. Your organisation may be developing their own cloud-based systems which would be ideal.

Keep your main store of digital images as a stand-alone digital collection; a ‘digital image repository’. You can then copy and alter/enhance any of these images as you need them, storing these additional copies separately or deleting them after use as appropriate.

Sample guidelines

Promotion of collections

Once digitised, visual materials can be used to showcase your Local Studies collection; for example Swindon Local Studies have placed digital copies of many of their photographs on Flikr

Images also make great content for social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Beware of copyright issues regarding the publication of images online – see the Copyright section of the toolkit for more information.

Images are also hugely important for exhibitions and presentations (these are generally exempt from copyright if used for educational purposes).

Harnessing the power of volunteers

Volunteers will prove invaluable to help you build up your finding aid catalogue and to digitise your collections but be aware that cataloguing is a particular skill that some volunteers may have trouble mastering and may need additional support. Areas that volunteers find especially problematic is the use of subject terms. Use a limited number of terms whilst asking other staff to add those as part of the checking process.

Projects

Here are a selection of presentations from the LSG South 2014 Study Day on Digitisation, together with the report from Local Studies Librarian

Got something to add?

Do you have any comments, suggestions or updates for this page? Add a comment below or contact us. This toolkit is only as good as you make it.

Other interesting projects that include images:

Know your place West of England includes the KYPWilts Postcards Project:

Got something to add?

Do you have any comments, suggestions or updates for this page? Add a comment below or contact us. This toolkit is only as good as you make it.

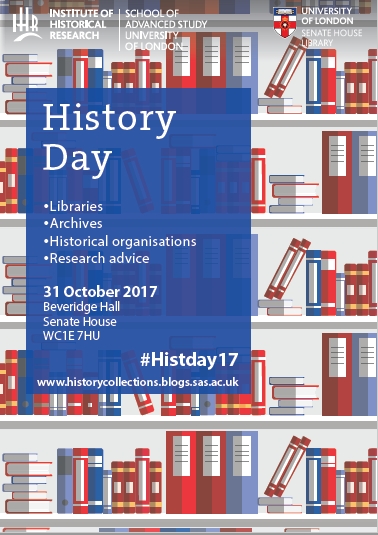

Institute of Historical Research and Senate House Library host an annual History Day. This year’s event is on 31 October 2017 at Senate House. The day is a way for libraries and archives to promote their collections and for students and researchers to find out about a range of historical collections in one place. Throughout the year we share blog posts about collections on the related History Collections website. A special theme this year given the date of History Day is ‘Magic and the supernatural’, but blog posts on any subject are welcome.

Institute of Historical Research and Senate House Library host an annual History Day. This year’s event is on 31 October 2017 at Senate House. The day is a way for libraries and archives to promote their collections and for students and researchers to find out about a range of historical collections in one place. Throughout the year we share blog posts about collections on the related History Collections website. A special theme this year given the date of History Day is ‘Magic and the supernatural’, but blog posts on any subject are welcome.